This blog

post aims to explain from my perspective how the course theory influenced our

project and the final design of the prototype. We would read theory from the

book and apply that knowledge through frameworks and suggestions the book had

to offer. All page numbers and chapters reference to the 1st edition of Interaction

Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction).

We started

off by conceptualising the problem space by attempting to answer the

following questions: (Ch 2, page 38)

- Are there problems with the existing solution (if that solution exists) ?

- Why do you think your proposed idea is useful?

- How will your proposed design support people in their activities ?

We also

used the conceptual model based on activities, mainly when we were designing

and coding the prototype. This conceptual model involved the user performing

activities such as:

- instructing

- conversing

- manipulating and navigating

- exploring and browsing

With this

model, we identified the main interaction a user would have with the

app. Those activities were manipulating

and navigating as well as exploring and browsing. This is because

our app involves users interacting with information and navigating through

different pages. There was no form of instructions the user could give the app

nor was there any conversing with the app.

Theory from

chapter 3 (Understanding Users) helped us deal with the psychology perspective

of the app. The idea of cognition (Ch 3, page 74) is important when designing an app

like ours because we wanted users to feel engaged and to pay attention while

exerting as little brain power as possible. When I coded the prototype, I kept

in mind that small details such as how the placement of buttons can affect a

user's interaction with the app. One issue in the first version of the

prototype was a back button I implemented. The button allowed you to return to

the previous page. The problem with this button was the way our pages were set

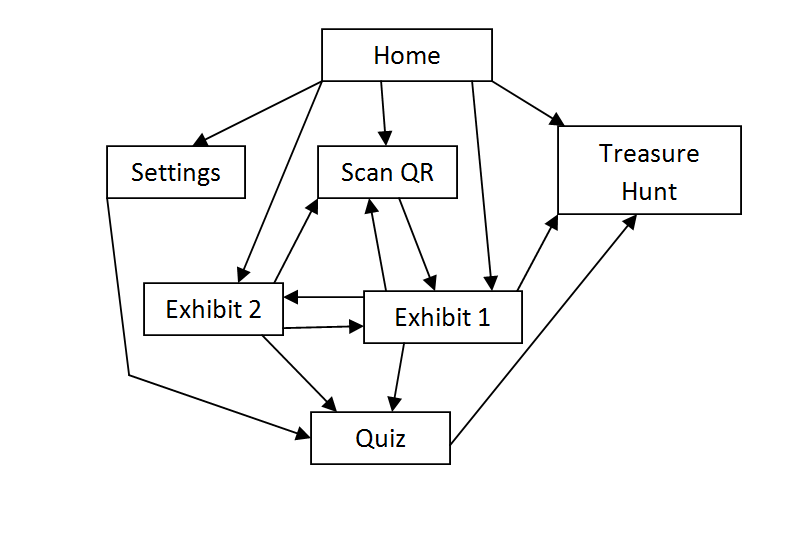

up. A hierarchy of the pages looks like this:

The issue

with the back button was that a user had to press it excessively to return to

the home page. The page layout is not linear but it is more like a web. There

are several links one can use to access different pages (such as buttons). If a

user were to navigate through ten pages for example, they would have to press

the back button ten times to return home. When we tested users and performed a think

aloud evaluation, this was a common issue that the users would complain

about. To fix this, I replaced the back button with a home button which reduced

the time it takes to return to the home page.

Information

presentation (Ch 3, page 76) was also a key influence to the prototype because of the app's reliance

on text based information. To ensure that everything was easy to read, font

sizes and spacing was applied in an appropriate manner.

In chapter

5 (Understanding how interfaces affect users), one particular aspect that we

could relate to was user frustration. All of us at some point have experienced

frustration with an app and this can cause a user to stop using it all together

(especially if there are better alternatives out there). The theory provided

several main causes of user frustration such as gimmicks, error messages,

overburdening the user and appearance.(Ch5, pages 148-153) The main sources of frustration

that was concentrated upon was gimmicks and the appearance. Some gimmicks

popped up in our user testing such as the "select language" button which did not actually change the language. However, coding

several languages into the prototype takes time and this was only a prototype

so this was not too much of an issue. However, the quiz had a

flaw where it would provide a pop-up

saying "Correct Answer" when a user selected any answer. This lead

them to a false sense of achievement until they realised the bug. This section on

user frustration helped us identify issues that users commonly have and helped

us prevent those issues from appearing in the final design.

In our exercise, we combined our conventional and non-conventional prototypes and in this process, we were able to identify the main requirements the app would need to fulfil. On page 207, "A user may be a novice, an expert, a casual or a frequent user" was a useful quote because it made me realise the importance of the user's skills. If we make the app too complex, it could be difficult for novices such as children and old people to understand the features. If the app was designed to be too simplistic with constant reminders on how to use the app, more advanced users may not find it as appealing to use. The aim was to instead, create something with a simplistic interface but if the user needed help, they could rely on the panel page. This page is opened by a button labelled "help" located at the top right of the home page. This way, a more advanced or frequent user who is familiar with the interface won't be annoyed by reminders on how to use the app.

There were several methods of obtaining data (questionnaires, interviews, workshops, natural observation and studying documentation) but we only used a select few. (Ch7, page 211) I believe that the most applicable form of data gathering was questionnaires and natural observation. Interviews are good to get in-depth analysis but finding willing participants would have been difficult. Questionnaires is what we used and participants would give us or short statements for their answers. Natural observation worked to a certain extent because we could observe physical interaction within the museum (a person interacting with a device). However the user's thought processes are harder to determine this technique.

Compromises in prototyping (Ch 8, page 246) is something that popped up when deciding how far the features were meant to be implemented. For example, the select language button simulates what it would be like to select the language but does not actually change it. We wanted to focus more on the design rather than implementing 6 different languages which could be done when the app actually gets made.

The evaluation paradigm we used was the "quick and dirty" paradigm . In the evaluation process, we just gave participants the prototype and wanted to see if they could figure it out for themselves. We did not use the usability testing paradigm because we would be controlling the evaluation. By having the users evaluating the app for themselves, they are able to spot potential flaws that we may have overlooked. (Ch 11, pages 340-343)

In our exercise, we combined our conventional and non-conventional prototypes and in this process, we were able to identify the main requirements the app would need to fulfil. On page 207, "A user may be a novice, an expert, a casual or a frequent user" was a useful quote because it made me realise the importance of the user's skills. If we make the app too complex, it could be difficult for novices such as children and old people to understand the features. If the app was designed to be too simplistic with constant reminders on how to use the app, more advanced users may not find it as appealing to use. The aim was to instead, create something with a simplistic interface but if the user needed help, they could rely on the panel page. This page is opened by a button labelled "help" located at the top right of the home page. This way, a more advanced or frequent user who is familiar with the interface won't be annoyed by reminders on how to use the app.

There were several methods of obtaining data (questionnaires, interviews, workshops, natural observation and studying documentation) but we only used a select few. (Ch7, page 211) I believe that the most applicable form of data gathering was questionnaires and natural observation. Interviews are good to get in-depth analysis but finding willing participants would have been difficult. Questionnaires is what we used and participants would give us or short statements for their answers. Natural observation worked to a certain extent because we could observe physical interaction within the museum (a person interacting with a device). However the user's thought processes are harder to determine this technique.

Compromises in prototyping (Ch 8, page 246) is something that popped up when deciding how far the features were meant to be implemented. For example, the select language button simulates what it would be like to select the language but does not actually change it. We wanted to focus more on the design rather than implementing 6 different languages which could be done when the app actually gets made.

The evaluation paradigm we used was the "quick and dirty" paradigm . In the evaluation process, we just gave participants the prototype and wanted to see if they could figure it out for themselves. We did not use the usability testing paradigm because we would be controlling the evaluation. By having the users evaluating the app for themselves, they are able to spot potential flaws that we may have overlooked. (Ch 11, pages 340-343)

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar